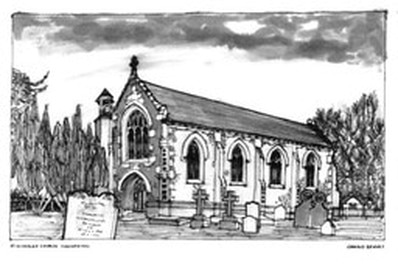

St Nicholas Cholderton

by Brigadier Michael Clarke MBE

Forward

This short history of St Nicholas, Cholderton makes use of a number of articles about the present church. It updates the fascinating Parish notes published by the then rector, the Rev'd Edwin Barrow, in 1889. It enlarges in to at part of the booklet about Cholderton which was produced for the Parochial Church Councils of the upper Bourne Valley in 1985 in order to provide visitors with guide to the most important features of those churches. And it is a thanks offering for the sixteen very full years which my wife and I have spent in the village.

It seems to me that the more people know about their church the more they are likely to take a pride in it and support it.

I have listed my sources of information in an annex. Most of the documents are lodged in the church for safekeeping and further reference. I am greatly indebted to their authors for the research which went into their production and which saved me much time and effort. My thanks also go to Christopher and Gill Love for their assistance in putting this history together. Without their help it would not have been completed.

October 1995 Michael Clarke

It seems to me that the more people know about their church the more they are likely to take a pride in it and support it.

I have listed my sources of information in an annex. Most of the documents are lodged in the church for safekeeping and further reference. I am greatly indebted to their authors for the research which went into their production and which saved me much time and effort. My thanks also go to Christopher and Gill Love for their assistance in putting this history together. Without their help it would not have been completed.

October 1995 Michael Clarke

History of the Church of St Nicholas, Cholderton

In 1971 the Council for the Care of Churches produced a report about the four churches of the Upper Bourne Valley for the Salisbury Diocesan Pastoral Committee which was then considering the possibility of uniting the benefices of all four parishes under a single incumbent and making one church redundant. Of St Nicholas, Cholderton the northernmost church of the group, the report said:

"To visit Cholderton is to recapture something of the pristine spirit of the Oxford Movement. The incumbent of the church at the time of its rebuilding was the Rev'd Thomas Mozley, friend of Newman, Keble and Pusey; Oriel College, Oxford, was patron of the living. The church is situated on the east side of the main road running through the village, placed towards the top of a fairly steep slope with cottages placed on either side of a gulley leading up to the church. Tall, un-aisled and (with the exception of its turret at the northwest corner) without a break from north to south to mark any internal division it looks exactly like a college chapel. Inside, this impression is reinforced by the stone screen separating the chapel from the ante-chapel at the level of the first bay from the west. The building is four bays long, dived externally by four buttresses and each bay contains a tall window of two cinquefoil-headed lights with a traceried head. The east window is a larger window, of three lights, and all have moulded labels supported on carved figure corbels. The building is flint-faced with a stone plinth; materials and design seem to be exactly fitted to one another.

The interior is magnificent, splendid in proportions, and everywhere enhanced by the quality of its fittings - the tiled floors, of exceptional richness, with the patterns changing from ante-chapel to nave and from nave to sanctuary; the stone screen separating the ante-chapel carved with a frieze of angels holding shields bearing the arms of Mozely, Oriel College, Roundell Palmer, Littlemore church etc.; the richly and inventively carved bench-ends of the pews; stone pulpit and font, with font-cover of wood; and most amazing of all , the roof itself of ten bays which Mozely is said to have found upon the quay at Ipswich, the relic of a monastic foundation, and had the church designed around it. The west door itself is extremely fine, with fine traceried divisions and carved crockets. In the ante-chapel is the bowl of the font from the earlier church, an Elizabethan Communion table, and a handsome monument with and informative inscription recording the career of Anthony Cratcherode, d. 1752

Bell: one, mediaeval inscribed "Santa Anna"

...Cholderton is an unjustly unsung masterpiece of the mid-19th century, of historical importance also in its link with the fountain head of the Oxford Movement..."

The oldest and smallest of the four churches is St Andrew's, Boscombe which dates from the 14th century. The other three, all with very old origins, were rebuilt in the 1840's. St Andrew's, Newton Tony in 1844, At John the Baptist at Allington between 1848 - 1850 and St Nicholas', Cholderton between 1841 and 1850 using the same architect, TH Wyatt, as at Newton Tony. But why did Cholderton take so long and why is it so different? The answer to the first part is a simple one - lack of funds - and to the second the dedicated enthusiasm of Thomas Mozley and his successor as rector - James Frazer, who later became Bishop of Manchester. It is a story worth telling.

"To visit Cholderton is to recapture something of the pristine spirit of the Oxford Movement. The incumbent of the church at the time of its rebuilding was the Rev'd Thomas Mozley, friend of Newman, Keble and Pusey; Oriel College, Oxford, was patron of the living. The church is situated on the east side of the main road running through the village, placed towards the top of a fairly steep slope with cottages placed on either side of a gulley leading up to the church. Tall, un-aisled and (with the exception of its turret at the northwest corner) without a break from north to south to mark any internal division it looks exactly like a college chapel. Inside, this impression is reinforced by the stone screen separating the chapel from the ante-chapel at the level of the first bay from the west. The building is four bays long, dived externally by four buttresses and each bay contains a tall window of two cinquefoil-headed lights with a traceried head. The east window is a larger window, of three lights, and all have moulded labels supported on carved figure corbels. The building is flint-faced with a stone plinth; materials and design seem to be exactly fitted to one another.

The interior is magnificent, splendid in proportions, and everywhere enhanced by the quality of its fittings - the tiled floors, of exceptional richness, with the patterns changing from ante-chapel to nave and from nave to sanctuary; the stone screen separating the ante-chapel carved with a frieze of angels holding shields bearing the arms of Mozely, Oriel College, Roundell Palmer, Littlemore church etc.; the richly and inventively carved bench-ends of the pews; stone pulpit and font, with font-cover of wood; and most amazing of all , the roof itself of ten bays which Mozely is said to have found upon the quay at Ipswich, the relic of a monastic foundation, and had the church designed around it. The west door itself is extremely fine, with fine traceried divisions and carved crockets. In the ante-chapel is the bowl of the font from the earlier church, an Elizabethan Communion table, and a handsome monument with and informative inscription recording the career of Anthony Cratcherode, d. 1752

Bell: one, mediaeval inscribed "Santa Anna"

...Cholderton is an unjustly unsung masterpiece of the mid-19th century, of historical importance also in its link with the fountain head of the Oxford Movement..."

The oldest and smallest of the four churches is St Andrew's, Boscombe which dates from the 14th century. The other three, all with very old origins, were rebuilt in the 1840's. St Andrew's, Newton Tony in 1844, At John the Baptist at Allington between 1848 - 1850 and St Nicholas', Cholderton between 1841 and 1850 using the same architect, TH Wyatt, as at Newton Tony. But why did Cholderton take so long and why is it so different? The answer to the first part is a simple one - lack of funds - and to the second the dedicated enthusiasm of Thomas Mozley and his successor as rector - James Frazer, who later became Bishop of Manchester. It is a story worth telling.

First Impressions

Thomas Mozley was a fellow of Oriel College. In 1835 he began to develop an interest in church architecture which he made his speciality when he was invited to write for the British Critic Magazine by his colleague and future brother-in-law, the Rev'd John Henry Newman, who was an Anglican minister until 1845 when he became a Roman Catholic; he became a priest in 1847 and his Eminence Cardinal Newman in 1879. In 1836, after his marriage to Harriet Elizabeth Newman, Mozely was appointed rector of the parish of St Nicholas, Cholderton. In a letter to her aunt dated 9th November 1836, Harriet conveyed her first impressions of Cholderton. She wrote:

"I am only just beginning to be a little settled, for tho' we seemed at home for the first hour and in no confusion, it is only the last day or two that I have got a proper cook. And as yet I do not find household cares very galling, but it is doubtful if I shall have things regular as I wish. I shall be of some little time getting into the system of the place, never having lived so entirely in the country and no means of getting around at present, beyond our feet. We have everything from Salisbury, 10 miles away, which is a serious inconvenience and always requires management. The village is very pretty, in a nest of fine trees, the parsonage is at one end of it near the church, which is the meanest and smallest that I know, except West Worldham. The house is a very comfortable, convenient one, neither small nor large. It is very warm and dry. The country about is as bare and uninteresting as one can imagine Salisbury Plain to be. We walked yesterday to the top of a high hill about 2½ miles off, and saw an extended view of the plain and bare hills, rather grand. We are, however, close by the Western road, and more than half the year a coach passes our gate. We have a good garden both flower and kitchen. I like my servants very much… I have had 8 or 9 calls. We should have had many more, but we have made known our keeping no carriage at present - this of course precludes all visiting. The population is very small, under 200, so that we shall soon know everybody. The people are very proud to have their Rector come to reside among them, and there is no doubt of our getting on well with them I think - they seem so friendly and tractable. My husband has called on nearly everybody and had a long talk with each… I hardly heard him preach till I came here. There has generally only been one sermon on Sunday. Now there will be two with a sermon and catechising alternately. The children are very well taught here. The S. School is kept by the clerk and his wife who are most respectable people. I never saw a place so universally comfortable and tidy. There is only one poor person here - yet wages are the same as elsewhere, only the people have learned to leave the public house and go to church. This has been done through the late curate, who nevertheless is a sporting and hunting clergyman… I have multitudes of letters to answer. We found a heap waiting for us. We are trying to make a change in the post, which is highly inconvenient and expensive to us. The Post Office is very obliging and promises immediately to see what can be done.”

"I am only just beginning to be a little settled, for tho' we seemed at home for the first hour and in no confusion, it is only the last day or two that I have got a proper cook. And as yet I do not find household cares very galling, but it is doubtful if I shall have things regular as I wish. I shall be of some little time getting into the system of the place, never having lived so entirely in the country and no means of getting around at present, beyond our feet. We have everything from Salisbury, 10 miles away, which is a serious inconvenience and always requires management. The village is very pretty, in a nest of fine trees, the parsonage is at one end of it near the church, which is the meanest and smallest that I know, except West Worldham. The house is a very comfortable, convenient one, neither small nor large. It is very warm and dry. The country about is as bare and uninteresting as one can imagine Salisbury Plain to be. We walked yesterday to the top of a high hill about 2½ miles off, and saw an extended view of the plain and bare hills, rather grand. We are, however, close by the Western road, and more than half the year a coach passes our gate. We have a good garden both flower and kitchen. I like my servants very much… I have had 8 or 9 calls. We should have had many more, but we have made known our keeping no carriage at present - this of course precludes all visiting. The population is very small, under 200, so that we shall soon know everybody. The people are very proud to have their Rector come to reside among them, and there is no doubt of our getting on well with them I think - they seem so friendly and tractable. My husband has called on nearly everybody and had a long talk with each… I hardly heard him preach till I came here. There has generally only been one sermon on Sunday. Now there will be two with a sermon and catechising alternately. The children are very well taught here. The S. School is kept by the clerk and his wife who are most respectable people. I never saw a place so universally comfortable and tidy. There is only one poor person here - yet wages are the same as elsewhere, only the people have learned to leave the public house and go to church. This has been done through the late curate, who nevertheless is a sporting and hunting clergyman… I have multitudes of letters to answer. We found a heap waiting for us. We are trying to make a change in the post, which is highly inconvenient and expensive to us. The Post Office is very obliging and promises immediately to see what can be done.”

The Rectory

The two storey rectory which Mrs Mozley found so agreeable was built over the years 1830-33 some 50 yards behind the site of the old parsonage. A field separated it from the old church which it would have dominated had it been closer. The broken ground of the field called Clump Meadow, had lead to the thought that it might be the site of the old British village. There had been a parsonage on the north side of it for many years. The register of incumbents of Cholderton begins with the year 1297 but they did not necessarily reside there.

The Parish Register Book records, for example that in 1651 “Mr Samuel Heskins was by the Lady Kingsmill presented to the Rectorie of Choldrington the 4th day of December in the year 1651 - and finding the parsonage House, the Barne, stable and all outhouses out of Repaire and almost fallen to the Ground thro’ neglect of the former Incumbent, who in the Civil War was some three years Absent from Choldrington and was never after Resident there, but dwelt at Sarum, because the parsonage-house at Choldrington was not Habitable, he, the said Mr Heskins at his own Cost and Charge began to Repaire and build up the dwelling-House, Barne, Stable and outhouses.”

The result appears to have been satisfactory and the house continued in use until 1721 when it was rebuilt. However the new one was so poorly constructed that in 1750 it was reported by a surveyor to be incapable of repair. It was not until 1829 that sufficient funds were forthcoming to repair it and at times the rector lived elsewhere. George Parry, for example, who was rector from 1747-68, does not have his name in the parish register for which that period records only those of a succession of curates who were obliged to live in the parsonage house. A new house was largely completed in 1830, with minor additions later, and it is that house which exists today. It is known as the Old Rectory, but is no longer a church house.

The Parish Register Book records, for example that in 1651 “Mr Samuel Heskins was by the Lady Kingsmill presented to the Rectorie of Choldrington the 4th day of December in the year 1651 - and finding the parsonage House, the Barne, stable and all outhouses out of Repaire and almost fallen to the Ground thro’ neglect of the former Incumbent, who in the Civil War was some three years Absent from Choldrington and was never after Resident there, but dwelt at Sarum, because the parsonage-house at Choldrington was not Habitable, he, the said Mr Heskins at his own Cost and Charge began to Repaire and build up the dwelling-House, Barne, Stable and outhouses.”

The result appears to have been satisfactory and the house continued in use until 1721 when it was rebuilt. However the new one was so poorly constructed that in 1750 it was reported by a surveyor to be incapable of repair. It was not until 1829 that sufficient funds were forthcoming to repair it and at times the rector lived elsewhere. George Parry, for example, who was rector from 1747-68, does not have his name in the parish register for which that period records only those of a succession of curates who were obliged to live in the parsonage house. A new house was largely completed in 1830, with minor additions later, and it is that house which exists today. It is known as the Old Rectory, but is no longer a church house.

The Old Church

Harriet Mozely’s disparaging description of the church was well founded. It was small, and very old. It was given to the prior and monks of St. Neot’s, a Benedictine monastery in Huntingdonshire, about 1175 by Roger Barnard and the grant was confirmed by Pope Alexander. Patronage of the living remained with the Priory until 1449 when it passed into secular hands. In 1692 it was sold, with the rectory, by Sir William Kingsmill to Thomas Coldwell who lived at Kimpton in Hampshire. He died in the next year and left them both to Oriel College Oxford, from where he had taken his MA degree in 1663. (He does not appear to have been a Fellow.)

The church measured 40 feet 2 inches by 16 feet 3 inches. The slab of the communion table was a foot below the level of the ground outside. The east wall was green with damp. The lighting was so bad that a skylight had been cut in the roof. What troubled the rector the most though were the square pews that almost filled the nave. It was the custom to allocate them to the more well-to-do families. In his reminiscences Mozley wrote:

“On Sundays they were almost empty while the old and infirm, the deaf and the half blind and helpless are sitting here and there under the gallery, in the darkness. The stouter labourers and all the lads, of an age to think themselves men, frequent the gallery. The children are in the passage - or they are in the chancel, sitting maybe on what should be a kneeling board for communicants.”

Before he ever went to Cholderton Mozley, in his articles in the British Critic, had adversely criticised the layout in the Protestant and Reformed churches which he considered placed too much emphasis in the most convenient method of seating the greatest number. He disliked galleries and urged his readers to prevent their erection. He urged the importance of space and simplicity of layout. “The east end”, he wrote, “Is apt to lose dignity from the number and smallness of its parts.”

He condemned flat plaster ceilings which were a feature of Gothic churches still being built in the 1830s. “The trouble was”, he said, “That architects grudged the extra money that an oak roof would cost, while wasting equal or greater sums on fussy ornaments.” He was reminded of his views by his Oxford friends when they visited him. In his reminiscences he later wrote: “My friends chaffed me on my church, and made invidious comparisons between it and the new rectory, which I have enlarged for my pupils… Something must be done… Moreover, the churches all about me were in a bad state, and I was there to set an example.” Thus he was provoked into action.

The church measured 40 feet 2 inches by 16 feet 3 inches. The slab of the communion table was a foot below the level of the ground outside. The east wall was green with damp. The lighting was so bad that a skylight had been cut in the roof. What troubled the rector the most though were the square pews that almost filled the nave. It was the custom to allocate them to the more well-to-do families. In his reminiscences Mozley wrote:

“On Sundays they were almost empty while the old and infirm, the deaf and the half blind and helpless are sitting here and there under the gallery, in the darkness. The stouter labourers and all the lads, of an age to think themselves men, frequent the gallery. The children are in the passage - or they are in the chancel, sitting maybe on what should be a kneeling board for communicants.”

Before he ever went to Cholderton Mozley, in his articles in the British Critic, had adversely criticised the layout in the Protestant and Reformed churches which he considered placed too much emphasis in the most convenient method of seating the greatest number. He disliked galleries and urged his readers to prevent their erection. He urged the importance of space and simplicity of layout. “The east end”, he wrote, “Is apt to lose dignity from the number and smallness of its parts.”

He condemned flat plaster ceilings which were a feature of Gothic churches still being built in the 1830s. “The trouble was”, he said, “That architects grudged the extra money that an oak roof would cost, while wasting equal or greater sums on fussy ornaments.” He was reminded of his views by his Oxford friends when they visited him. In his reminiscences he later wrote: “My friends chaffed me on my church, and made invidious comparisons between it and the new rectory, which I have enlarged for my pupils… Something must be done… Moreover, the churches all about me were in a bad state, and I was there to set an example.” Thus he was provoked into action.

The New Church

Mozley brought his ideas to TH Wyatt, who was the consulting architect to the Salisbury Diocesan Church Building Association. He had already acquired a roof for his new church and the design had therefore to fit in with it. He had heard about the roof when visiting friends in Suffolk. It was lying on the quay at Ipswich. In Norman times there had been at Ipswich an order of Augustinian monks whose house, probably built before 1200, was the monastery of SS Peter and Paul. There seems little doubt that this roof once covered their dining room. After the Reformation and the Dissolution of the Monasteries it was acquired by a guild of clothing workers, who cut their guild sign of shears into the wood. On the decline of the woollen trade their hall was demolished, and the roof placed on the Ipswich quay. It measured 80 feet by 20 feet 6 inches. Mozely bought it and arranged for it to be conveyed to Cholderton by sea, canal and turnpike. He also brought a small number of Suffolkcarpenters and wood carvers to the village whom he employed to fashion the roof for its new purpose and to construct the pews. He obtained a New Forrest oak for £30 for the purpose, from a timber yard where it lay on the point of being delivered to a naval shipyard. He had to buy additional land to extend the churchyard, on which the roof was reassembled on the north side of the old church. His wife, writing to her aunt in September 1840, complained:

“There is an immense barn shed roof and workmen which just spoils our view of the goings on from the house.”

Mozley took the design of the west door from the Tower Church at Ipswich and the shape of the windows from the church at Old Basing, but it was always the roof that was the major consideration. Wyatt had little confidence in the strength of the structure and tied every truss with iron bolts to bind the woodwork. Mozley for his part was afraid that the high walls which he needed might bulge, and so it was decided to bury iron bars, hooked together, in the masonry above the windows. He had begun to collect other materials in the summer of 1840. Early in September Newman who continued to take a keen interest in the project wrote that Mozley had 20,000 bricks in his churchyard and that his people were dispersed over Salisbury Plain gathering flints. He bought stone from Tisbury and sand from the other side of Salisbury at two guineas a load. He had to fill a chalk pit in the enlarged churchyard by carting in spoil from half a mile away. He was very much his own builder and clerk of works, greatly helped by his gardener, Thomas Meacher, of whom he wrote:

“He managed all my earthworks, haulage, gathering of flints from the hills and sand from the roadside, lodging the work people and countless other matters.”

The foundation stone was laid by Harriet Mozley on 29th April 1814. Three months later Mozley wrote to his brother James, who was coming on a visit:

“We have the additional attraction of the church building, which is now about six feet above ground. I shall require the breathing space afforded me by making a two year job of it as by 20th August, when I stop operations, I shall be on the verge of bankruptcy.”

However the work continued in the following year. He was earning extra money by editing the British Critic and Harriet was writing children’s stories which were selling well. By the early summer of 1843 the roof had been assembled and the walls were up to half the height of the windows. But work did not stop then because of lack of funds.

Although there had been great interest in the new church it did not translate into financial support. In his Parish Notes of Cholderton which were published in 1889 the Rev’d Edwin Barrow lists all the donors. The only local ones were rectors in the area, at Netheravon, Amesbury, Tidworth and Idmiston and Thomas Meacher who managed ten shillings. Mozley later wrote that no help came from Lady Nelson, who was Lady of the Manor and the largest land owner, or from any of the farmers, or from Assheton Smith of Tidworth who hunted the district and dominated its society. Oriel College donated £100 which might have perhaps been more had the Provost been less reluctant to approve the plans for the church. Many of the fellows also subscribed individually and seven members of the Mozley family also contributed. Even so the total donated was less than £1000 and the cost in the end came to over £6000 which Mozley had to find almost entirely by his writing.

One reason for the lack of financial support by those who were able to contribute seems to have been the proposed open plan seating. Archibald Paxton, the recently arrived tenant of Cholderton House, and some local farmers had strong objection to it. In an article about pews Mozley wrote by way of illustration:

“A gentleman rents a mansion of the date of Queen Anne… He may be considered a squire. Well, a church or chapel-of-ease is to be built, and he demands a distinguished square pew in accordance with his own rank and station and with the property that he occupies. The four hunting farmers with pianos in their drawing rooms do the same.”

Paxton persisted with his objections and threatened legal action. Eventually some years later, he was pacified by the offer of an L - shaped pew at the front of the nave in which he could sit with his back to the wall, and thus avoid having people breath down his neck which apparently was his main concern. The pew was in due course installed, and is still in position today.

When the work on the church stopped in 1843 Mozley was thoroughly depressed. He recalled:

“There I stood penniless - my wife was in ill health and visiting friends; my only servant was the gardener. I was in debt on the church account mainly to the village blacksmith, living on bread, butter, cheese and garden stuff.”

When Harriet returned home she was still unwell so he borrowed £50 on the autumn tithe account and took her to Brittany for a long holiday. He returned in September, resolved to end his troubles by joining the Roman Church, but Newman persuaded him to put off a decision for two years. He had resigned from the British Critic and now started writing for The Times. He kept his benefice, engaged a curate to do most of the work, and with a salary of £1,800 a year in addition to his stipend he was able to start work on the church again. For more than three years he was half journalist, half rector and builder, but he found his position increasingly unsatisfactory. In the autumn of 1846 there was a severe outbreak of fever in the village which caused many deaths and added greatly to his cares. In 1847, with the village recovered, he resigned Cholderton, albeit with immense regret, and went to work in London.

His successor James Fraser, appointed by Oriel College, was unmarried and had his Fellowship and an allowance from his parents to supplement his meagre stipend. Mozley continued to pay for the building of the church, and Fraser consulted him about difficulties and sent regular reports. There had been considerable progress on the church during the previous year. In her correspondence Harriet Mozley refers, in March 1846, to workmen “coming back from Suffolk this week to go on with the church” and in October to the scaffolding coming down, the carving outside the church being finished. The walls, exactly one yard thick, had been faced with flints, cut and set in courses and here and there in patterns, displaying superb workmanship. A light fir roof between the oak roof and the tiles gave a sharper pitch to the exterior. The carved roof bosses and the heads on the outside of the walls were the work of stone carvers previously employed on the new church at Wilton. Two of them on the north side, are of Thomas and Harriet Mozley. Of the two charming angels on the east end one represents their daughter Grace. Of them Harriet wrote in a letter to her sister dated 30th October 1846:

“I have been busy this week at the church directing Grace’s figure and face which Mr Howitt has been executing for an angel… It is now enough for one of the workmen removing the scaffolding to have remarked “That face is so like Mrs Mozley’s that I should have thought it was done for her.” Anyhow it is a pretty little thing, and with its companion, also from Grace’s attitude and expression, the gem of the carved work as yet.”

With the walls completed and the roof on there was much for Fraser to attend to inside the church. The stone screen separating the ante-chapel from the nave was decorated with shields in heraldic colours displaying the armorial bearings of many people who were connected with the parish, the Mozley family and the Oxford movement at the time (see annex). In December 1847 two wagon loads of flooring tiles arrived from the Minton works. They had been specially made, and the design was shown at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. The pews were made of oak; the pew ends, all different, represent the fruits of the earth, a theme which was repeated in the coving of the cornice outside.

Mozley had supported the cause of the Free Trade in articles in The Times and when it was introduced he commemorated the occasion by having the pew ends carved to portray the Free Gifts of God to Man. The idea of the L-shaped pew to appease Mr Paxton came from a similar shaped pew at the new church in Newton Toney. Fraser also had a new, larger font of Caen stone with a cover of oak built, more suited in size to the larger church. In this he was at odds with Mozley, who wished to keep the old font, as medieval builders always did. There was also controversy between them over the windows. Fraser submitted a complete plan for the painted windows which the Mozleys sent back by return of post, so alarmed were they by the cost. But Fraser persisted and Mozley and his family found the money.

It took Fraser ten years to complete the installation of the windows, long after the consecration of the new church by Edward Denison, Bishop of Salisbury, which took place on the 10th April 1850. Fraser had written to Harriet Mozley the previous month to say that the church was finished and that he had reserved three bedrooms at the Rectory for her party. The weather was fine, the ceremony went off very well. There was a parish dinner after it in the rectory meadow which cost the Rector £40, and the Bishop’s coach man told Meacher that of all the consecrations that eh had attended there was nothing like Cholderton.

It was not until the following March that the old church was pulled down. The walls of the nave were in good condition and provided much excellent material for the village school that Fraser was building just outside the lych-gate on land presented by Countess Nelson. For nearly a year the two churches stood side by side. The new one twice as high and twice as long as the old one.

“There is an immense barn shed roof and workmen which just spoils our view of the goings on from the house.”

Mozley took the design of the west door from the Tower Church at Ipswich and the shape of the windows from the church at Old Basing, but it was always the roof that was the major consideration. Wyatt had little confidence in the strength of the structure and tied every truss with iron bolts to bind the woodwork. Mozley for his part was afraid that the high walls which he needed might bulge, and so it was decided to bury iron bars, hooked together, in the masonry above the windows. He had begun to collect other materials in the summer of 1840. Early in September Newman who continued to take a keen interest in the project wrote that Mozley had 20,000 bricks in his churchyard and that his people were dispersed over Salisbury Plain gathering flints. He bought stone from Tisbury and sand from the other side of Salisbury at two guineas a load. He had to fill a chalk pit in the enlarged churchyard by carting in spoil from half a mile away. He was very much his own builder and clerk of works, greatly helped by his gardener, Thomas Meacher, of whom he wrote:

“He managed all my earthworks, haulage, gathering of flints from the hills and sand from the roadside, lodging the work people and countless other matters.”

The foundation stone was laid by Harriet Mozley on 29th April 1814. Three months later Mozley wrote to his brother James, who was coming on a visit:

“We have the additional attraction of the church building, which is now about six feet above ground. I shall require the breathing space afforded me by making a two year job of it as by 20th August, when I stop operations, I shall be on the verge of bankruptcy.”

However the work continued in the following year. He was earning extra money by editing the British Critic and Harriet was writing children’s stories which were selling well. By the early summer of 1843 the roof had been assembled and the walls were up to half the height of the windows. But work did not stop then because of lack of funds.

Although there had been great interest in the new church it did not translate into financial support. In his Parish Notes of Cholderton which were published in 1889 the Rev’d Edwin Barrow lists all the donors. The only local ones were rectors in the area, at Netheravon, Amesbury, Tidworth and Idmiston and Thomas Meacher who managed ten shillings. Mozley later wrote that no help came from Lady Nelson, who was Lady of the Manor and the largest land owner, or from any of the farmers, or from Assheton Smith of Tidworth who hunted the district and dominated its society. Oriel College donated £100 which might have perhaps been more had the Provost been less reluctant to approve the plans for the church. Many of the fellows also subscribed individually and seven members of the Mozley family also contributed. Even so the total donated was less than £1000 and the cost in the end came to over £6000 which Mozley had to find almost entirely by his writing.

One reason for the lack of financial support by those who were able to contribute seems to have been the proposed open plan seating. Archibald Paxton, the recently arrived tenant of Cholderton House, and some local farmers had strong objection to it. In an article about pews Mozley wrote by way of illustration:

“A gentleman rents a mansion of the date of Queen Anne… He may be considered a squire. Well, a church or chapel-of-ease is to be built, and he demands a distinguished square pew in accordance with his own rank and station and with the property that he occupies. The four hunting farmers with pianos in their drawing rooms do the same.”

Paxton persisted with his objections and threatened legal action. Eventually some years later, he was pacified by the offer of an L - shaped pew at the front of the nave in which he could sit with his back to the wall, and thus avoid having people breath down his neck which apparently was his main concern. The pew was in due course installed, and is still in position today.

When the work on the church stopped in 1843 Mozley was thoroughly depressed. He recalled:

“There I stood penniless - my wife was in ill health and visiting friends; my only servant was the gardener. I was in debt on the church account mainly to the village blacksmith, living on bread, butter, cheese and garden stuff.”

When Harriet returned home she was still unwell so he borrowed £50 on the autumn tithe account and took her to Brittany for a long holiday. He returned in September, resolved to end his troubles by joining the Roman Church, but Newman persuaded him to put off a decision for two years. He had resigned from the British Critic and now started writing for The Times. He kept his benefice, engaged a curate to do most of the work, and with a salary of £1,800 a year in addition to his stipend he was able to start work on the church again. For more than three years he was half journalist, half rector and builder, but he found his position increasingly unsatisfactory. In the autumn of 1846 there was a severe outbreak of fever in the village which caused many deaths and added greatly to his cares. In 1847, with the village recovered, he resigned Cholderton, albeit with immense regret, and went to work in London.

His successor James Fraser, appointed by Oriel College, was unmarried and had his Fellowship and an allowance from his parents to supplement his meagre stipend. Mozley continued to pay for the building of the church, and Fraser consulted him about difficulties and sent regular reports. There had been considerable progress on the church during the previous year. In her correspondence Harriet Mozley refers, in March 1846, to workmen “coming back from Suffolk this week to go on with the church” and in October to the scaffolding coming down, the carving outside the church being finished. The walls, exactly one yard thick, had been faced with flints, cut and set in courses and here and there in patterns, displaying superb workmanship. A light fir roof between the oak roof and the tiles gave a sharper pitch to the exterior. The carved roof bosses and the heads on the outside of the walls were the work of stone carvers previously employed on the new church at Wilton. Two of them on the north side, are of Thomas and Harriet Mozley. Of the two charming angels on the east end one represents their daughter Grace. Of them Harriet wrote in a letter to her sister dated 30th October 1846:

“I have been busy this week at the church directing Grace’s figure and face which Mr Howitt has been executing for an angel… It is now enough for one of the workmen removing the scaffolding to have remarked “That face is so like Mrs Mozley’s that I should have thought it was done for her.” Anyhow it is a pretty little thing, and with its companion, also from Grace’s attitude and expression, the gem of the carved work as yet.”

With the walls completed and the roof on there was much for Fraser to attend to inside the church. The stone screen separating the ante-chapel from the nave was decorated with shields in heraldic colours displaying the armorial bearings of many people who were connected with the parish, the Mozley family and the Oxford movement at the time (see annex). In December 1847 two wagon loads of flooring tiles arrived from the Minton works. They had been specially made, and the design was shown at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. The pews were made of oak; the pew ends, all different, represent the fruits of the earth, a theme which was repeated in the coving of the cornice outside.

Mozley had supported the cause of the Free Trade in articles in The Times and when it was introduced he commemorated the occasion by having the pew ends carved to portray the Free Gifts of God to Man. The idea of the L-shaped pew to appease Mr Paxton came from a similar shaped pew at the new church in Newton Toney. Fraser also had a new, larger font of Caen stone with a cover of oak built, more suited in size to the larger church. In this he was at odds with Mozley, who wished to keep the old font, as medieval builders always did. There was also controversy between them over the windows. Fraser submitted a complete plan for the painted windows which the Mozleys sent back by return of post, so alarmed were they by the cost. But Fraser persisted and Mozley and his family found the money.

It took Fraser ten years to complete the installation of the windows, long after the consecration of the new church by Edward Denison, Bishop of Salisbury, which took place on the 10th April 1850. Fraser had written to Harriet Mozley the previous month to say that the church was finished and that he had reserved three bedrooms at the Rectory for her party. The weather was fine, the ceremony went off very well. There was a parish dinner after it in the rectory meadow which cost the Rector £40, and the Bishop’s coach man told Meacher that of all the consecrations that eh had attended there was nothing like Cholderton.

It was not until the following March that the old church was pulled down. The walls of the nave were in good condition and provided much excellent material for the village school that Fraser was building just outside the lych-gate on land presented by Countess Nelson. For nearly a year the two churches stood side by side. The new one twice as high and twice as long as the old one.

The Windows

Fraser began in 1850 by installing the windows in the chancel, and the west window in the ante-chapel. Those on the north and south sides of the nave were inserted in 1858 and 1859, and the side windows in the ante-chapel in 1860. The great windows at the east and west ends of the church were made by the London firm, O’Connor of 4 Berners Street. Those on the north and south sides were by a less renowned establishment at Mells, near Frome, except for the two pairs in the chancel which were made by Clutterbuck of Stratford-le-Bow, Essex. There was no great difference in their price, from £55 to £62 for each pair of lights, but the quality seems to have varied. It is noticeable that the chancel side windows have begun to bulge in their frames, which will necessitate taking them out and re-leading them.

The east window of three lights represents the Agony, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection. Below in the centre light, is a medallion of St. Nicholas, depicting the legend of the Raising of the Children from the Salting-tub. (Having heard that a wicked butcher had murdered two children and thrown their bodies into a vat of pickling brine, the Saint prayed over them, whereupon they were restored to life.) In the lower compartments of the side lights are representations of the Faithful Centurion and of the Lawyer not far from the Kingdom of God, themes that were chosen in remembrance of two brothers Fraser, one a soldier the other a law student, who died in 1840 and 1847 both at the age of twenty. The side windows of the chancel represent on the north side the Fall of Manna and Moses striking the Rock, and on the south side the miracles of the Feeding of the Five Thousand and of the Water made Wine.

In the Nave one of the windows of two lights on the north side represents the Healing of the Lunatic Child and the Healing of Blind Bartimeus. The other depicts the healing of the Paralytic and Peter walking on the Sea. This window is in memory of Captain Edward Fraser of the Bengal Engineers “who in the revolt of the Bengal Native Army fell by the hand of his own mutinous troops whom he was endeavouring to recall to their duty at Meerut, India, May 16th, 1857.” He was the youngest brother of the Rector. On the south side one window of two lights represents the healing of the Woman with the Issue of Blood and the Anointing of the Penitent Woman. The other shows the offering of the Widow’s Mite and Christ blessing little Children. In the ante-chapel on the north side one window depicts the Prodigal Son and the Good Shepard, and the other one on the south side the Appearance to the two Disciples at Emmaus and Christ Standing at the Door and Knocking.

The east window of three lights represents the Agony, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection. Below in the centre light, is a medallion of St. Nicholas, depicting the legend of the Raising of the Children from the Salting-tub. (Having heard that a wicked butcher had murdered two children and thrown their bodies into a vat of pickling brine, the Saint prayed over them, whereupon they were restored to life.) In the lower compartments of the side lights are representations of the Faithful Centurion and of the Lawyer not far from the Kingdom of God, themes that were chosen in remembrance of two brothers Fraser, one a soldier the other a law student, who died in 1840 and 1847 both at the age of twenty. The side windows of the chancel represent on the north side the Fall of Manna and Moses striking the Rock, and on the south side the miracles of the Feeding of the Five Thousand and of the Water made Wine.

In the Nave one of the windows of two lights on the north side represents the Healing of the Lunatic Child and the Healing of Blind Bartimeus. The other depicts the healing of the Paralytic and Peter walking on the Sea. This window is in memory of Captain Edward Fraser of the Bengal Engineers “who in the revolt of the Bengal Native Army fell by the hand of his own mutinous troops whom he was endeavouring to recall to their duty at Meerut, India, May 16th, 1857.” He was the youngest brother of the Rector. On the south side one window of two lights represents the healing of the Woman with the Issue of Blood and the Anointing of the Penitent Woman. The other shows the offering of the Widow’s Mite and Christ blessing little Children. In the ante-chapel on the north side one window depicts the Prodigal Son and the Good Shepard, and the other one on the south side the Appearance to the two Disciples at Emmaus and Christ Standing at the Door and Knocking.

Later Developments

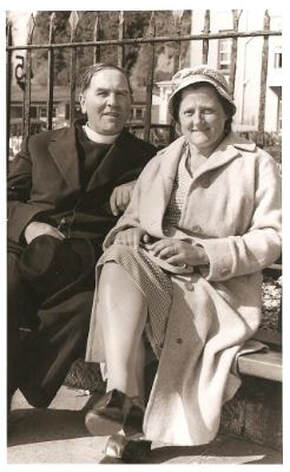

Rev'd Bryan Bishop and his wife Bess

Rev'd Bryan Bishop and his wife Bess

Incumbents of Cholderton from 1297 - 1889 are listed in the ante-chapel. Since then there have been:

1883 AE Brisco Owen

1917 GE Hope

1918 William King

1972 Francis Chesterman

1924 Frank McGowan

1978 John Harvey

1955 Bryan Bishop

1982 Geoffrey Davies

1970 Pelham Hopkins

1990 Peter Burtwell

In 1889 Henry C Stephens MP of Cholderton Lodge, Hants, acquired by purchase the manor and estate in Cholderton until then in the possession of Rear-Admiral The Honourable Maurice Horatio Nelson. He bequeathed the village hall and recreation ground in trust to the village when he died in 1923. He was buried in the vault below the chancel and his body was later transferred to the family mausoleum in the churchyard when it was built in 1926.

The organ was built by the Positive Organ Company of Hanover Square, London, and was dedicated on 8th October 1905. It was given by Mr and Mrs Stephens and the Rector, the Rev’d AE Brisco Owen.

Pendant lamps suspended from the roof were the main source of lighting until they were removed after electricity was installed in 1932. A new arrangement of light bulbs in 1995 has greatly improved visibility of the carvings on the roof timbers. The guild sign of the clothing workers of Essex can now be seen.

In 1926 a large boiler was installed in the vault below the chancel it supplied hot water to pipes which extended the length of the aisle. This system of heating was replaced by electric wall heaters in 1960, and was augmented by under pew heating in the front five pews on each side in 1986.

Recent Years

1950 was the centenary year of the present church. The church was re-decorated, and was treated for death watch beetle, traces of which had been found in the roof and the flooring. The Bishop of Salisbury, the Right Reverend Dr. Anderson, preached at evensong in October as part of the centenary celebrations. It was the first year of a decade which seems to have been a high tide in church affairs. The Reverend Frank McGowan had been Rector since 1924. He had now become the Venerable Archdeacon of Sarum but remained Rector until 1955. The village school at the entrance to the church yard flourished, and so did the village shop and post office at the bottom of Church Lane. The People’s Warden throughout the decade was Air Commodore Andrew Walser of Cholderton House, who had married into the Stephens Family and who was a staunch supporter of the church until his death in 1966 when he was buried in the family mausoleum. In 1957 Lord Marchwood, at the Manor became the Rector’s Warden, and Lady Marchwood became a foundation manager of the school. The church was very much the centre of the village affairs.

In 1955 when Rev'd Bryan Bishop and his wife Bess arrived

there were 47 names on the church electoral roll. By 1960 the numbers had increased to 84. This was due to two events. One was the Representation of the Laity measure of 1956 which lowered the age limit for inclusion on the roll from 18 to 17 to encourage young people to take an active part in the life of the church. It also permitted a person to have his name entered on two rolls in the same diocese, with the consent of the Parochial Church Councils concerned.

The other event was the extension of the church parish across the county boundary into Hampshire under an order in Council dated the 21st June 1955. The Diocesan authorities of Winchester and Salisbury were at the time discussing the rearrangement of the parish boundaries adjacent to county borders. Cholderton PCC maintained that the occupants of Park House and the neighbouring habitations had always been cared for by the Rector of Cholderton, and their children attended the Cholderton Aided School (No. 3320), whereas the Shipton Bellinger parish school was further away and was not a parochial school. The PCC’s case was accepted, and later, in 1960, the ecclesiastical boundary was further extended to include Thruxton Farm and dwellings on the Grately Road.

The boundary changes increased the adult population of the parish from about 160, which had prevailed since the 1830’s to over 200. However in 1987 there was another review of boundaries, this time by the Local Government Boundary Commission for England. Both Salisbury District Council and Cholderton Parish Meeting recommended that the civic parish boundary of Cholderton should be extended to coincide with the ecclesiastical one because Cholderton village was the focal point of the area and electors living on the Hampshire side looked upon Cholderton as their village. The review body felt that was insufficient justification, in terms of effective and convenient local government, for it to happen, so the anomaly has remained.

During the 1960s numbers of the church electoral roll remained in the Eighties but this healthy state was not reflected in the financial side. It was a perpetual struggle to meet the costs of heating and lighting bills, repairs to the church roof, and the upkeep of the churchyard. The main event of the period was the construction of a new rectory in the glebe field in place of the old one, which was larger than necessary and a drain on limited diocesan resources to maintain. The new one was completed in October 1967 and was dedicated by the Bishop of Salisbury in 24th March 1968. The old one was bought by Colonel Peter Gibbs, the Princess Royal’s Secretary. He lived there until 1994.

In January 1970, soon after incurring substantial costs on repairs to the church roof, the PCC was warned that the church spire was in a dangerous condition and should be repaired as soon as possible. Of the two options presented, taking down the bell tower completely would be less expensive but might damage the corner of the church, complete restoration would cost a great deal more. A compromise was therefore agreed, which was to demolish the tower to the base of the belfry, and to erect above the base a structure which would enable the bell to be rung. The work was completed in 1973, the tower was made safe and the bell rang again.

Another difficult matter for the parish during those early years of the 1970s was pastoral reorganisation which the PCC had been warned in March 1972 was being considered and which might if implemented, result in the parish loosing its resident rector. This came about when the Bourne Valley Team Ministry was set up by an Order in Council made on 29th March 1973. The new benefice of the Bourne Valley Team Ministry was to consist of the parishes of Allington with Boscombe, Cholderton, Newton Tony, Idmiston with Porton and Gomeldon, Winterbourne Earls and Dauntsey and Winterbourne Gunner. The clergy were to be a Team Rector and two Team Vicars. They were to reside in the parsonage houses at Porton, Cholderton and Winterbourne Earls, but the house at Allington was substituted for Cholderton as being more convenient for the priest caring for the four northernmost churches. The office of Team Rector was to be held for seven years and that of Team Vicars for a period not exceeding seven years.

The timing was unfortunate for Cholderton where there had been three changes of Rector in as many years. The Rev’d Bryan Bishop departed in February 1970 and was succeeded by the Rev’d Pelham Hopkins, ex RAF, in December. His induction had been arranged for the 11th of that month but he was too ill to attend the church service and it was carried out by the Bishop of Salisbury in the Rectory. He died in January having been unable to take a service. The Rev’d GE Hope was installed in August 1971, but he chose to resign in September 1972 when the Team Ministry was due to begin functioning. The Rev’d Robin Ray was appointed Deacon in Charge of Boscombe, Allington, Newton Tony and Cholderton until his ordination which was due in two years time, and he moved with his family into the Cholderton Rectory. He found the cost of living very high for his miniscule stipend, and he left the Bourne Valley Team in 1976 after he was ordained priest. His successor occupied Allington Vicarage and Cholderton Rectory was sold and renamed The Brake.

The lack of continuity among incumbents had adverse consequences. The minutes of the Annual Parochial Church Meeting in March 1977, at which the Team Rector took the chair, recorded that there was a lack of interest in the church services and the state of the church in general. There were seven people present, and the Electoral roll stood at 37. That the church kept going at all was largely due to the schoolmaster Mr Glyn Jones. He was a Lay Reader who frequently took the services in church and chaired the PCC meetings, in many discreet ways he also helped the impoverished deacon. He was supported by three dedicated ladies, his wife Beryl, Mrs Jenkinson, PCC Secretary, and Mrs Rayment, Treasurer. The grateful appreciation of him by the parish was publicly expressed some years later when a plaque to his memory was placed on the refurbished lych-gate.

The late 1970’s were also a time of increased expenditure on the fabric of the church when it could least be afforded. In 1977 it was decided to erect clear Perspex sheeting on the outside of the side windows in the chancel to protect the glass in them from further deterioration. In 1980 redecoration of the interior of the church could be delayed no longer. A difficult decision had to be made about the band of biblical texts on the walls of the nave below the window cills. Expert advice was to the effect that the process of restoration would be very costly and time consuming and would create unpleasant chemical fumes while it was taking place. It was therefore decided to paint over them, leaving a plain wall. It was also decided to leave untouched the wall decorations behind the altar, and to conceal them behind a curtain.

A further blow was the closure of the church school, so conveniently located for Sunday School and meetings of the PCC, and a constant reminder to parents and pupils of the existence of the church. It was closed in 1978 because of reduced attendance and the children of the village had to travel to the Church of England Primary School at Newton Tony. When the Cholderton School had opened in 1851 to number of children entered was 16. Numbers soon increased to over 30, but they began to decline again in the 1970’s and were down to 17 at time of closure. Parents no longer had to pass the village shop and post office at the bottom of Church lane which ceased to be financially viable and this too closed in 1980.

Closure of the school was one indication of the changing nature of the village. It could no longer be called agricultural for there were few jobs to be had on the land, or for that matter in the village. The proximity of good rail and road communications facilitated commuting to work and the paucity of public transport necessitated car ownership. The availability of low cost rented accommodation declined as the right to buy council houses took hold. Agricultural cottages were bought and converted into retirement or weekend houses. There were many newcomers to the village; the big houses were changing hands. The village was fast becoming an outward looking commuter community for whom time at home at weekends was precious. In keeping with the national trends church attendance as a matter of duty was no longer regarded as important. Nevertheless the PCC, reinforced and broad based, found itself taking the initiative to encourage a village community spirit as well as attending directly to affairs of the church. The 1980’s saw a revival of interest in the church and a strong improvement in its financial state. The tide had turned.

In 1980 there came financial help from an unexpected source when Mr. Young a former resident of Cholderton and owner of the Poldark Mine Wishing Well in Cornwall, donated its contents to the PCC. He brought them with him in sacks of coins, mainly copper, which amounted to £950. It is said that the vicar undertook to pay them into the bank and incurred a parking ticket while doing so! Financial stability was regained over the decade by self help, much improved collection and covenant giving, generous support by the village at the annual summer fete and Christmas bazaar. Self help took many forms. It included voluntary cleaning of the church and graveyard maintenance, and payment by the PCC members themselves for a variety of items such as new hymn books, under pew heating, provision for cremated remains and a new lightning conductor for the church.

The willingness to help was not confined to the PCC and is illustrated by the restoration of the churchyard from its overgrown state. Colonel Gibbs placed gates in the fences of The Old Rectory and the churchyard to provide access for his tractor grass mower, Mr. Ronnie Clark of Drybrook and his gardener planted hundreds of bulbs, trees and flowering shrubs in the north-east corner, and lavender bushes round the church. He brought in machinery to scrape clear the surface of the remaining uncleared strip of the churchyard on the south side, and re-seeded it. That part is now visibly a few inches lower than the rest of the churchyard. A remembrance garden for cremated remains was created in the southwest corner and Mrs. Jean Morgan made and planted a well stocked border of flowers and shrubs along the boundary with St. Nicholas Cottage.

It was also Jean Morgan who charted the graves. She located 571 in all and identified most of them. Among them is that of a benefactor of the school and the village poor, Anthony Cracherode, who died in 1752, and is commemorated by a marble tablet in the wall of the ante-chapel. There is also the tomb of Archibald Paxton. Despite his earlier quarrels with Mozley he enjoyed his Wiltshire home and became much involved with the life of the country. He died in 1875 at his London house, but was buried at Cholderton and his wife Elizabeth, who lived at Cholderton House, was laid to rest beside him on her death in 1887.

Reminders of the past of a different nature were evoked by visits from the USA of descendants of the Rev’d William Noyes. He was Rector of Cholderton from 1601 to 1621. He was succeeded by his son Nathan, who later became Chaplain-in-Chief to the Duke of Marlborough’s forces during the Low Countries campaign. He had two other sons, James and Nicholas who sailed to New England in 1634 in the ship “Mary & John” soon after the Mayflower. One settled in New England and the other headed west. At Cholderton church the visitor’s book provides details of 67 of their descendants who visited Cholderton in the years 1956 - 1991. More continue to come each year. A consolidated list of their addresses is maintained by the PCC secretary who is able to put them in touch with the Noyes family in this country. A Communion Set, a chalice and paten, in use at the church is inscribed “Presented in 1883 by James Noyes BA Harvard, and Penelope Barher Noyes, descendants of Rector Noyes BA Oxford 1592”. The Bronze altar cross is inscribed “In memory of Rev’d William Noyes Rector of Cholderton 1602 - 1622 To the Glory of God this gift is made by his descendant E H Noyes Easter 1894”.

Another link with the past is the Finchley Society. Before Henry Stephens purchased the Cholderton Estate he was a prominent and respected resident of Finchley in North London and Member of Parliament for the constituency. When he came to Cholderton he left his Finchley house to the Borough of Finchley, and his interest in, and benefactions to, Finchley are remembered and fostered by the Finchley Society, which visited Cholderton in 1995. The visit included the church, the Stephens, Now Edmunds, family mausoleum and the village hall which is part of the Henry Stephens benefaction to the village.

The village war memorial erected after the first World War was on trust land by the village hall and carried no names. They were listed in the ante-chapel of the church. The war memorial was moved to its present position by the Cholderton Estate in 1983 as a planning condition of the development of land behind the village hall for residential purposes. In 1995 the memorial was additionally inscribed to include World War II. The memorial commemorates 19 men from the village who gave their lives in 1914-18 and 3 during the 1939-45 war. The numbers reflect the proportion of casualties sustained nationally during the two wars.

The Future

In 1979 doubts about the suitability of the Bourne Valley configuration of villages for a Team Ministry caused the Bourne Valley Team Council to consider whether group status should be sought whereby each of the three parish groups would have its separate identity and Incumbent, and the team would cease to exist as a legal entity. A different question about the team was raised in 1983, when the Reverend Patrick Towers left the Winterbournes where he had combined his parish with the post of Archdeaconry Youth Chaplain, as to whether by implication three full-time priests were needed in the Bourne Valley. Much consideration was given to these matters in 1986 by Archdeaconry and Deanery Pastoral Committees, and that year the Alderbury Deanery Synod debated proposals for making greater use of lay pastoral assistance. The Synod concluded that they could make a valuable contribution in urban areas but in the country parishes the existing tradition of care and neighbourliness might be stifled. There was disappointment when it was decided that the Bourne Valley Team Ministry should continue. There was concern that the appointment of a new Team Rector in 1980 was accompanied by a condition that the Team should work out a pattern of services that could be maintained by two priests and a deacon or other team worker.

The initiative to reduce the number of priests in the Bourne Valley Team from three to two was prompted by a decline in the number of suitable applicants for ordination in the wider church. It later became a financial issue as well. In 1957 the Cholderton parish quota or parish share of the contributions levied on parishes to meet the cost of Ministry was £25. In 1980 it was £205 and in 1990 it was £1,264. The exceptional growth in the 1980s was due to the decline in the size of the Church Commissioners’ grants to the Diocese caused in part by the need to give priority to less affluent urban dioceses and to the growing cost of clergy pensions. Salisbury Diocese necessarily moved to self sufficiency.

Whether parishes can meet the full cost of Ministry remains to be seen. Relatively they are not high. In Cholderton, as in many small rural communities, there is a strong feeling that the church needs to be preserved as part of the village heritage. In Cholderton newcomers who make the effort to attend church services are assured of a warm welcome, coffee in the ante-chapel afterwards, and the acceptance through getting to know them which might not easily otherwise happen. The church is the heart of the community

Annex

Heraldic Shields

On the east face of the screen separating the ante-chapel from the nave, observed from left to right (i.e. North to South):

1 Rev’d Isaac Williams - Tractarian (the shield contains a representation of Littlemore Church Oxford)

2 Rev’d F A Tremonger - Curate at Cholderton 1846 - 47

3 John Mozley and his wife - the arms are those of Newman

4 Charterhouse School - where Thomas Mozely was educated

5 Anthony Cracherode

6 Francis Elizabeth, the Countess Nelson (the shield contains the word Trafalgar and shows a palm tree between a disabled ship and a ruined battery)

7 The United Kingdom

8 Edward Denison - Bishop of Salisbury 1836 - 54 - the arms are those of the See of Sarum

9 Henry Thornton - Tractarian, married to Miss S Mozley

10 Rev’d S Richards - Tractarian (the arms include those of his father-in-law, Sir Robert Wilmot of Chaddesden, Derby)

11 Rev’d Thomas Mozley and Harriet his wife, nee Newman

On the west face of the screen

1 Henry and John Mozley

2 Frederic Rogers, later Lord Blackford - Tractarian

3 Roundwell Palmer - Tractarian, later Lord Chancellor, Earl of Selbourne

4 Rev’d James Frazer, Later Bishop of Manchester

5 Oriel College, Oxford (the lions of England)

6 Unknown

7 The United Kingdom

8 The See of Sarum

9 Rev’d F W Fowle - married to Miss F Mozley

10 Rev’d F J Blandy and Rev’d R W Church, later Dean of St Paul’s

11 Miss A E Dyson and Mis A Mozley

Bibliography

The Churches of the upper Bourne Valley - booklet published in 1985

Council for the care of Churches Report - on the above churches, dated 12/71

Cholderton Church and its Builder - article by RG Gibson in the Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 70/71 (1978)

Parish Notes of Cholderton by Edwin P Burrow MA - dated 19/02/1889

Letters written by Harriet Mozley - given to the Rev’d Frank McGowan in 1952/53 when he was Rector of Cholderton

Notes on Cholderton Church - found with school papers

Inventory of Church Goods (“Terrier”) of St Nicholas Cholderton from October 1929

Cholderton and Newton Tony Parish News - September 1969

Archibold Frederick Paxton (1793-1875) article by Archibold Paxton 1993

Cholderton PCC Minute Book - Nov 1954 to Nov 1970

Cholderton PCC Minute Book - Dec 1970 to Oct 1995

The Probable Roots of the Noyes Family prior to 1786 and other material by EM Noyes of Guildford in 1991-94

A Note about the Laity Measure (1956) which amended Electoral Roll regulations dated 10/01/1959

Codicils to the Will of Mrs A M Stephens, relating to the upkeep of the Mausoleum

Alterations to the Parish boundary, Order in Council dated 24/06/1955 and map

Loan to the Rev’d Frank McGowan by the Governors of the Bounty of Queen Anne for the augmentation of the Maintenance of the Poor Clergy dated 01/01/1930 for the repairs to the parsonage house and paying diocesan costs

Plurality Order authorising one incumbent to hold the benefice of Cholderton and Newton Tony dated 31/07/1953

Local Government Boundary Commission for England - Report No 580

Parish Magazine for June 1995 - visit of the Finchley Society

Chart of the Graves in the Churchyard and list of names, completed in 1993

PCC Members since 1980 († Since died)

Jane Campbell-Johnson Left village in 2005

Terry Cull 2005- , Secretary 2005-’07, Electoral Roll officer 2006-09, Deanery synod 2007-

John Bennet 1983 -1989, left village

Bryan Chitty† Sidesman

Patricia (Paddy) Chitty Churchwarden 1985 - 1995, (Continuing member 2010)

Michael Clark MBE Treasurer 1982, Churchwarden 1989, Deanery Treasurer 1987, Diocesan Board of Finance 1987, Diocesan Synod 1993, left village in 1995

Mollie Clarke MBE Secretary 1979 - ’95 left village 1995

John Eddison Churchwarden from 1995

Triç Eddison Secretary from 1996

Kathleen Dent† left village 1994

Donald Fussey

Sally Gibbs 1978-’94, left village 1994

Michael Holliday Left village 20??

Ethel Jenkinson† Secretary 1995-’79, left village 1983, died ‘85

Glyn Jones† Lay Reader died 1998

Beryl Jones Continuing member (2010)

Rex Kearley 1970-’85, Churchwarden 1982-‘85

Shirley Kearley† 1970-’85, Electoral Roll officer 1975-‘85

Christopher Lowe JP 1990-’96, Diocesan Stewardship Adviser

Gillian Love Secretary 1995-’96, left village ‘96

Bruce McDowell Churchwarden 1982-’89, Treasurer 1995-??

Ruth McDowell

Ian Park-Weir Member (to date), Diocesan Synod Rep 2007-‘08

Priscilla Park-Weir Treasurer

Pearl Rayment† Churchwarden 1967-’82, Treasurer 1976-’82, died April 1988

Crawford Stoddart Churchwarden and Secretary to date

Timothy Taylor 1981-’83, left village ‘83

Ann Taylor 1982-’83 left village ‘83

Geoff Thomas 1991-’96 left village 20??

Gordon Whittick 1983-’89 left village

1 Rev’d Isaac Williams - Tractarian (the shield contains a representation of Littlemore Church Oxford)

2 Rev’d F A Tremonger - Curate at Cholderton 1846 - 47

3 John Mozley and his wife - the arms are those of Newman

4 Charterhouse School - where Thomas Mozely was educated

5 Anthony Cracherode

6 Francis Elizabeth, the Countess Nelson (the shield contains the word Trafalgar and shows a palm tree between a disabled ship and a ruined battery)

7 The United Kingdom

8 Edward Denison - Bishop of Salisbury 1836 - 54 - the arms are those of the See of Sarum

9 Henry Thornton - Tractarian, married to Miss S Mozley

10 Rev’d S Richards - Tractarian (the arms include those of his father-in-law, Sir Robert Wilmot of Chaddesden, Derby)

11 Rev’d Thomas Mozley and Harriet his wife, nee Newman

On the west face of the screen

1 Henry and John Mozley

2 Frederic Rogers, later Lord Blackford - Tractarian

3 Roundwell Palmer - Tractarian, later Lord Chancellor, Earl of Selbourne

4 Rev’d James Frazer, Later Bishop of Manchester

5 Oriel College, Oxford (the lions of England)

6 Unknown

7 The United Kingdom

8 The See of Sarum

9 Rev’d F W Fowle - married to Miss F Mozley

10 Rev’d F J Blandy and Rev’d R W Church, later Dean of St Paul’s

11 Miss A E Dyson and Mis A Mozley

Bibliography

The Churches of the upper Bourne Valley - booklet published in 1985

Council for the care of Churches Report - on the above churches, dated 12/71

Cholderton Church and its Builder - article by RG Gibson in the Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine 70/71 (1978)

Parish Notes of Cholderton by Edwin P Burrow MA - dated 19/02/1889

Letters written by Harriet Mozley - given to the Rev’d Frank McGowan in 1952/53 when he was Rector of Cholderton

Notes on Cholderton Church - found with school papers

Inventory of Church Goods (“Terrier”) of St Nicholas Cholderton from October 1929

Cholderton and Newton Tony Parish News - September 1969

Archibold Frederick Paxton (1793-1875) article by Archibold Paxton 1993

Cholderton PCC Minute Book - Nov 1954 to Nov 1970

Cholderton PCC Minute Book - Dec 1970 to Oct 1995

The Probable Roots of the Noyes Family prior to 1786 and other material by EM Noyes of Guildford in 1991-94

A Note about the Laity Measure (1956) which amended Electoral Roll regulations dated 10/01/1959

Codicils to the Will of Mrs A M Stephens, relating to the upkeep of the Mausoleum

Alterations to the Parish boundary, Order in Council dated 24/06/1955 and map

Loan to the Rev’d Frank McGowan by the Governors of the Bounty of Queen Anne for the augmentation of the Maintenance of the Poor Clergy dated 01/01/1930 for the repairs to the parsonage house and paying diocesan costs

Plurality Order authorising one incumbent to hold the benefice of Cholderton and Newton Tony dated 31/07/1953

Local Government Boundary Commission for England - Report No 580

Parish Magazine for June 1995 - visit of the Finchley Society

Chart of the Graves in the Churchyard and list of names, completed in 1993

PCC Members since 1980 († Since died)

Jane Campbell-Johnson Left village in 2005

Terry Cull 2005- , Secretary 2005-’07, Electoral Roll officer 2006-09, Deanery synod 2007-

John Bennet 1983 -1989, left village

Bryan Chitty† Sidesman

Patricia (Paddy) Chitty Churchwarden 1985 - 1995, (Continuing member 2010)

Michael Clark MBE Treasurer 1982, Churchwarden 1989, Deanery Treasurer 1987, Diocesan Board of Finance 1987, Diocesan Synod 1993, left village in 1995

Mollie Clarke MBE Secretary 1979 - ’95 left village 1995

John Eddison Churchwarden from 1995

Triç Eddison Secretary from 1996

Kathleen Dent† left village 1994

Donald Fussey

Sally Gibbs 1978-’94, left village 1994

Michael Holliday Left village 20??

Ethel Jenkinson† Secretary 1995-’79, left village 1983, died ‘85

Glyn Jones† Lay Reader died 1998

Beryl Jones Continuing member (2010)

Rex Kearley 1970-’85, Churchwarden 1982-‘85

Shirley Kearley† 1970-’85, Electoral Roll officer 1975-‘85

Christopher Lowe JP 1990-’96, Diocesan Stewardship Adviser

Gillian Love Secretary 1995-’96, left village ‘96

Bruce McDowell Churchwarden 1982-’89, Treasurer 1995-??

Ruth McDowell

Ian Park-Weir Member (to date), Diocesan Synod Rep 2007-‘08

Priscilla Park-Weir Treasurer

Pearl Rayment† Churchwarden 1967-’82, Treasurer 1976-’82, died April 1988

Crawford Stoddart Churchwarden and Secretary to date

Timothy Taylor 1981-’83, left village ‘83

Ann Taylor 1982-’83 left village ‘83

Geoff Thomas 1991-’96 left village 20??

Gordon Whittick 1983-’89 left village